As debate rages around the loosening of restrictions and recreational travel bans here in Australia, one thing is glaringly obvious; in this instance, we have clearly proven to be, the Lucky Country.

Latest data from the World Health Organisation (WHO) tallying the number of new cases and fatalities around the globe, clearly demonstrates that Australia’s rate of infection has been markedly less than many other developed nations.

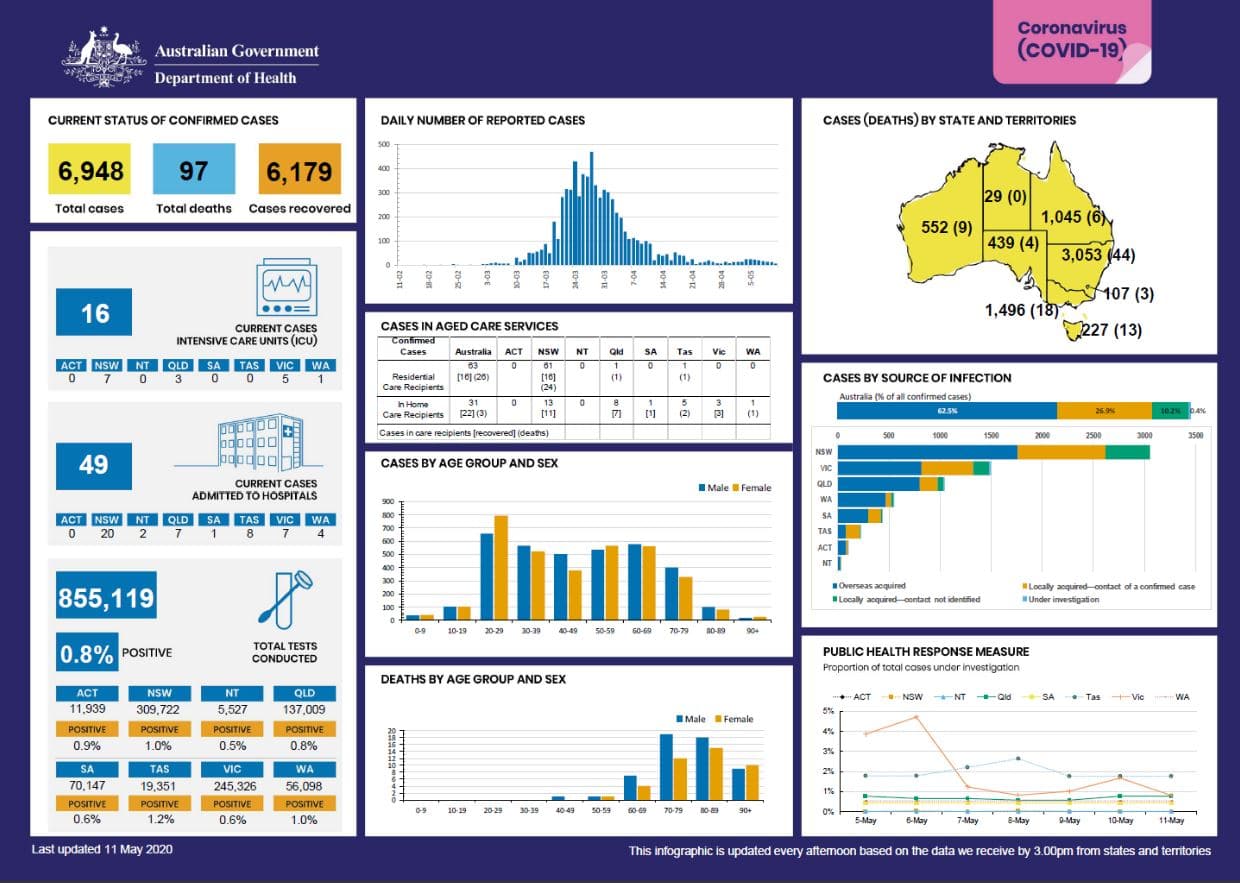

Since the Coronavirus scare escalated in March, we’ve had a total of 97 deaths reported, and have been one of the most successful countries to “flatten the curve” substantially, even though our lockdown restrictions were comparably lenient than those in other places.

We are also one of the few places in the world that’s seen a marked de-escalation in new cases recently, alongside China, New Zealand and parts of Africa and Central America.

The numbers at a glance

COVID-19 was first confirmed in Australia in late January, since which time we’ve reported a total of 6,948 cases and only 97 fatalities.

While the below table shows that the majority of infections reported were slightly higher for females aged between 20-29 years, those who’ve died have largely been over the age of 70.

Interestingly, the data around “Cases by Source of Infection” clearly demonstrates that the majority of those testing positive in Australia, actually acquired the infection from overseas origins; at 62.5 per cent compared with around 37 per cent from local contact within this country.

The number of cases and deaths have also been markedly higher in New South Wales, compared to other states and territories, with the state’s figures accounting for almost half of all positive tests and fatalities.

When our numbers are presented side by side with other countries, it’s glaringly obvious that we’ve been largely sheltered from a more severe outbreak of the pandemic than most.

The number of reported cases in the US for instance, was over one million according to the WHO yesterday, with the total number of deaths sitting at close to 77,000.

Across Europe, Spain, Italy, the UK and France were among the hardest hit by the viral outbreak, with fatalities totalling around (or slightly higher than) 27,000 in each country, largely due to community transmission.

Somewhat ironically, in the alleged epicentre of the COVID-19 pandemic – China – there have been less reported cases and far fewer deaths than across the United States and parts of Europe, with the total number of fatalities reported at 4,643 as of last week.

Why have some places been hit harder?

While many of the theories regarding why COVID-19 has been far more virulent in spreading throughout some countries than others – including Australia – are based largely on conjecture versus hard evidence, one of the more plausible conclusions is lifestyle. More specifically, the type of dwellings we tend to occupy and how broadly or compactly various populations live.

Locally, Aussies are renowned for our love of McMansions and large sprawling suburban blocks, as opposed to higher density, apartment type dwellings. When it comes to our population density, we average just 3 people per square kilometre.

Compare this to New York City – one of the locations that’s seen the most rampant spread of COVID-19, and where there are an estimated 10,194 people per square kilometre.

While the population density in the UK, France, Italy and Spain is nowhere near that of New York, at 281, 119, 206 and 94 residents per square kilometre respectively, these areas are all known for their higher density way of life and far more multi-level apartment buildings.

Has lower density living been our saving grace?

Not only are we blessed with a far greater land mass than total population (and are relatively more socially distanced from the rest of the world), our tendency to gravitate more toward detached housing as a cultural and social norm, has also potentially helped to shelter us from the COVID-19 storm other nations have succumbed to.

This means less chance for person to person transmission of the virus through avenues like shared communal areas and elevators, which are of course prevalent features in apartment living; particularly in the type of high rise buildings traditionally found across places like New York City.

In the early days of the pandemic, research suggested one of the primary surfaces where the virus survived the longest was stainless steel, where the WHO reported it was able to survive for up to 72 hours.

When you contemplate that the majority of elevator buttons and other surfaces peppered throughout communal areas of apartment buildings are stainless steel, you can’t help but wonder if this contributed to the spread in some of the worst impacted cities, compared to the relative minimal outbreak here in Australia.

Monash University professor of medicine Paul Komesaroff said while more densely populated areas did have a greater risk for spreading the disease, if people followed social distancing measures and common apartment areas were thoroughly cleaned, managing the contagion would be easier.

He also speculated that, in the likes of Italy for instance, culture has played a larger role in spreading the virus than higher density living.

“That includes being in close physical contact when they greet, but also extended families meeting for dinner and grandparents looking after grandchildren and so on. The contact really relates to deep features of the culture, not just whether people are in the same high-rise building,” he told Domain.

Should we ditch higher density development?

Experts suggest that while higher density living could have contributed to some of the higher incidences of cases and deaths we’ve seen from COVID-19, we shouldn’t necessarily throw out the baby with the bath water.

Director of EG Urban Planning Shane Geha, said people shouldn’t fear living in medium to high-density neighbourhoods, which he claims can actually be more beneficial for our health in the long term compared to Australia’s urban sprawl model.

“Public transport cannot work without density,” he said. “The low density city models have a terrible effect on pollution, on sprawl, on car dependency.”

RMIT University professor and planning expert Billie Giles-Corti said while the rapid spread and subsequent deaths from COVID-19 have been tragic, millions more die each year from chronic health conditions such as heart disease and diabetes.

“Globally there are 15.2 million deaths due to heart disease and stroke, there are 1.6 million people a year who die from diabetes two. These are massive numbers, and that is partly because of the risk factors for those diseases and a big part of that is being physically inactive,” Professor Giles-Cortis said.

“The way we design our cities makes a huge difference, so a denser city means that we do have all the benefits of density – access to public transport, the potential for more affordable housing, people can walk and cycle to local shops.”

Professor Giles-Cortis said if executed correctly, density was a positive for cities not only from a health perspective but from an environmental one, and potentially makes for more resilient populations.

“I don’t think we should throw the baby out with the bathwater thinking, ‘oh a dense city means that we’re going to have more disease’ – that is completely not true. It’s about the strategies we put in place to control the virus – social distancing, stay at home, these sorts of things,” she said.

In the meantime, I think we can all agree that our wide open spaces and less compact way of life, have been a blessing in disguise at this time. And we are indeed, The Lucky Country.