Over the last century or so, our collective social psyche has hinged on a few iconic ideals about what it means to be ‘an Aussie!’

Right at the top of the list, along with football, meat pies, kangaroos and Holden cars, is the cultural norm that’s arguably become the intrinsic bedrock of our economic wellbeing…the Great Australian Dream.

You know the one…the dream of home ownership.

That definitive dream most hard working men and women have harboured since around the middle of last century, toiling so that they may one day ‘have it all’ in the form of a dwelling in suburbia that sees them through financially in retirement.

But what happens when the nation undergoes a cultural shift of significant proportions? What happens when you no longer revere the kangaroo as your national symbol, but feed it to your pets? When Holden is no longer a true blue Aussie brand? And when meat pies are replaced with wholefood wraps and lattes?

Well, as we’re now witnessing in this new technological revolution that comes with a much faster pace of life and infinitely more complexities, the Great Australian Dream starts to disintegrate.

So what?

Some might think this isn’t much of a big deal, and may even argue that although the ideal of home ownership is dwindling, there’s more activity stimulating today’s property markets than ever before.

But the fact is, bricks and mortar investment has always been as safe as houses in this country for one primary reason – the majority of the market was in the hands of homeowners. Some 70 plus per cent in fact.

That meant stability. Because when times got a little tough, we weren’t all inclined to flood the markets in a bid to offload our own homes. And let’s face it, ‘selling up’ has always been perceived as a sign of ‘selling out’ among our society.

But if you happened to have a spare property or two lying around and needed to free up cashflow for whatever reason, the holiday home or secondary investment was fairly disposable.

A new world order

I’m not sure exactly when, where or how the transition took place. But at some stage, our Great Australian Dream underwent a serious overhaul. Blame it on affordability issues, over-indulged younger generations who refuse to start out in modest digs like their parents, tax perks for property investors, or world events like the GFC.

Whatever scapegoat you fancy, the bottom line is that housing has become more about acquiring an asset, than a home and hearth, since the turn of this century.

Now, our long held love of property is imperilling our economic stability. The very foundation we’ve built our financial fortunes on is starting to look shaky.

The predominant issue is that we’re currently facing the highest levels of household debt in our brief history. On its own, that’s surely cause for concern. But when you drill down into the distribution of that debt, the story becomes even more troubling.

Are investors a pesky property invader?

It all started close to a decade ago now, when the GFC left many reeling in financial destitution and seeking a safer place to park their money than the many decimated managed super funds at the time.

Real estate looked like a lovely option, particularly as you could use the equity in your own home to start out. And there were a lot of ‘property investment experts’ who’d made millions, sharing their get rich stories so others could do the same.

Plus, with governments stimulating activity through first homebuyer incentives, property markets were looking ever more resilient and secure, as local housing values steadily chugged along without any major corrections in our country.

The investor onslaught began in earnest however, when the Reserve Bank started slashing interest rates in a bid to stimulate property markets and pick up the economic slack from a then ailing resource sector, around five years ago now.

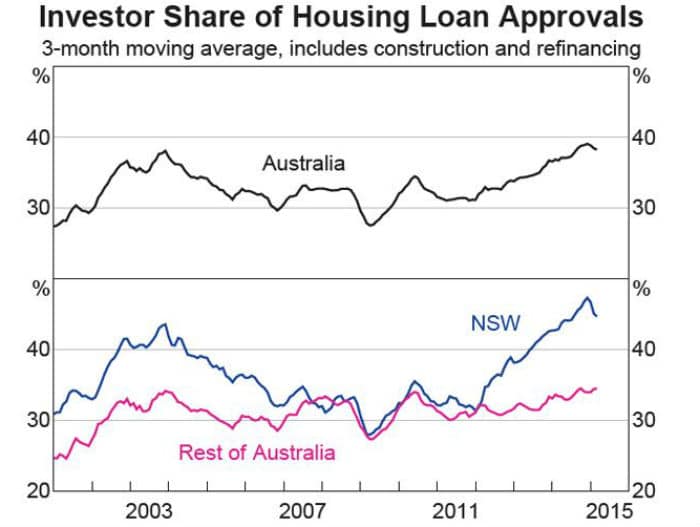

Today, investors account for around 40 per cent of all new housing loans nationally. And in New South Wales, almost half of all buying activity is attributed to people purchasing secondary assets.

We know that in some of the seriously fast paced Sydney property sectors; first homebuyers have been all but pushed out of contention. This means that now, and into the foreseeable future (unless something drastic changes), we’re seeing an increasing proportion of households with investment properties.

This shift in property ownership dynamics heralds a very different landscape for our housing markets. Why? Because that attachment to the properties we borrow money to buy is diminishing.

At present, the banks have more than $1.5 trillion in outstanding home loans on their collective books. $1.5 trillion! Over one third of that has been lent to investors…the grand sum of $543 billion.

Less than a decade ago, when the Australian Prudential and Regulatory Authority (APRA) started gathering home loan data, the total value of all mortgages in this country was $683 billion.

Is it still safe?

The fact is, we’ve all been backed into somewhat of a corner by lenders, who’ve happily thrown money at people clamouring to take advantage of rising markets in the context of cheap housing credit.

Regulators are becoming increasingly concerned at the amount of large interest only and equity heavy loans that have been dished out over the last five years. Hence, the latest moves from APRA to once again staunch the flow of capital from our banking sector.

Many suggest that should a downturn or some economic catalyst (be it local or global) occur now, investors could conceivably start dumping their assets, even in light of a comparably modest correction by historical standards.

So you see, as we’ve made the increasing correlation between housing as a commodity in this country, lending for investment in property has virtually become as risk loaded as the share market from a banking perspective.

Essentially, it could be said that we’re on a very similar precipice as we were just before the GFC; only this time the mechanism is more likely to be a housing market correction.

Cast your mind back to when the banks were throwing margin loans at anyone with a savings account to buy shares, some 15 odd years ago. Stocks were booming back then so shares were the place to be for many investors.

It was easy…if the dividends failed to cover the interest on your loans, you simply wrote off your losses via negative gearing, and then repaid the money when you sold your stocks for squillions. But then the wheels fell off globally. And stocks began to tank.

Of course lenders were forced to sell off the shares they held as security when investors could no longer cover the paper losses on their portfolios, compounding the troubles of a stockmarket that was on the brink of a serious free fall.

You’d think the banks would have learnt their lesson…short memory, as Peter Garrett would lament.

Back on the banks

Regulators are currently coming down hard on lenders, insisting the banks must shore up their capital caches, in case the housing market turns a less than desirable corner in the near future.

It’s not surprising really, given the amount of risk exposure we’re already talking about when it comes to the Australian financial services sector.

The debt attached to our banks is around 40 times the size of equity in the business. Compare this to the average debt to equity ratio of non-financial Aussie businesses at around 0.8.

And the majority of the banks’ debt exposure is in local real estate, with around 60 per cent of all loans related to home lending.

Further, when the sector was deregulated and deposit taking institutions were free to decide, independent of regulators, how much cash buffer they needed in case of a property downturn, they collectively did away with their cash reserves.

Safe as houses after all! So by 2014, the ‘risk weighted asset ratio’ was slashed from 50 per cent in 2007 to just 16 per cent.

Of course the regulators have now pulled the reins in once more to reverse this policy, but the fact is we’re still living with the consequences.

In short, the answer to whether property investment is still ‘as safe as houses’, if you have any common sense whatsoever, is not really. At least not at face value.

No longer, as investors, can we simply purchase a property and trust that time and compounding will work their magic to make us money.

The banks are being accused of failing to adequately protect themselves from the effects of a potential downturn. That’s the bottom line. In other words, the onus falls on each of us to be a responsible investor and make sure we have sufficient contingencies in place to weather any storms that might lie ahead.

We shouldn’t live in fear of the ‘what if’ scenarios, but we should absolutely account for them in our planning if we hope to create sustainable, long term investment portfolios.