Notoriously outspoken regarding Australia’s so-called housing affordability crisis and a staunch critic of the negative gearing policies he believes to be the catalyst for over-inflated property values, Saul Eslake seemingly did a 360 recently, on the back of new evidence that our property markets may actually be undervalued.

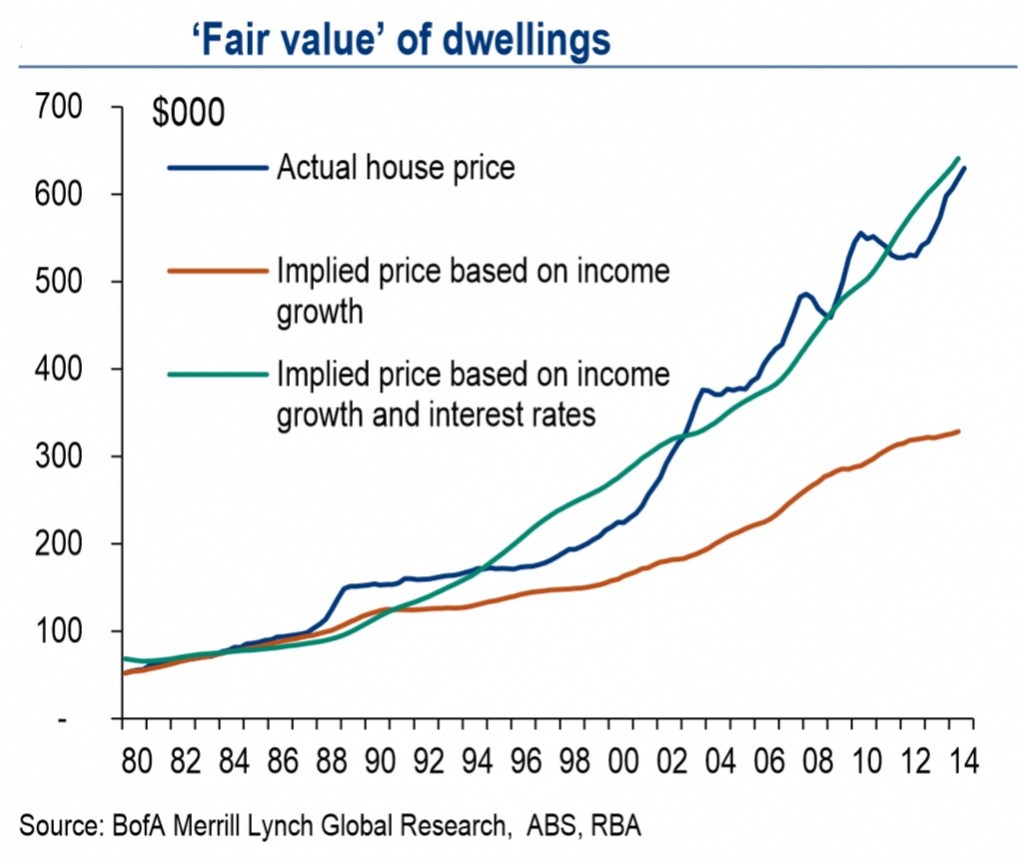

Merrill Lynch’s chief economist released a chart earlier this month that indicates the overall median house price in Australia is actually below implied price, based on income growth and interest rates – see below.

Speaking to Business Insider, Eslake said an anticipated 3.5 to 4% increase in values across 2015, with no change to interest rates, would cause house prices to “converge with ‘fair value’ estimates based on household income growth and mortgage rates.”

He adds that when the RBA starts lifting the cash rate in 2016, as most economists predict, we could witness a deceleration or possible decline in real prices.

Affordability not “the issue”

Eslake’s backflip and the data used to support his revised stance on the state of Australia’s housing markets, makes the argument of affordability as a major driver of the property sector in isolation somewhat moot, with an emphasis instead on changes to household income along with interest rates as primary influencers.

Of course, this chart also causes one to question the validity of scaremongers’ claims that inflated house prices are causing a bubble.

While there will be some critics who favour price-to-income measures as an isolated indicator, the fact remains that you can’t really talk about housing affordability without weighing up all of the interconnected factors at play and logically, that includes interest rates – as is obvious by the increase in market activity off the back of our current, low rate environment.

More at play

Much ado has been made of the disparity between ‘disposable household income’ and property prices in the past, with this often cited as direct evidence that house prices in Australia are dangerously inflated.

While it’s true that median property prices are now as high as six times the average disposable household income, this fact alone is not enough to draw conclusions about affordability.

In order to shed clearer light on what is actually occurring with regard to house prices, independent analyst Arek Drozda says we need to look at several key influences and how they interplay including;

1. Incomes. With a better indicator being double income households as opposed to general ‘disposable household income’ data that accounts for the averages based on every Australian – employed or not, which is not really a true representation of affordability.

Why? Because for a start, most households that don’t have at least one full time breadwinner are unlikely to secure a home loan and therefore, do not accurately represent the average Aussie homebuyer.

2. Rental prices. These are required in order to compare the relative cost of accommodation, since renting is the only other option as opposed to becoming an owner-occupier.

3. Cost of buying. With loan sizes getting bigger and loan terms getting longer, cost of buying is not just about the initial purchase price, with much more consideration given to the ongoing cost of owning property for the long term, including interest repayments, council rates, maintenance and so forth.

When you start to drill down into these measures, the affordability debate requires a lot more detail and analysis than the simplistic ‘disposable household income to property price ratio’ commonly referred to by many media commentators and analysts.

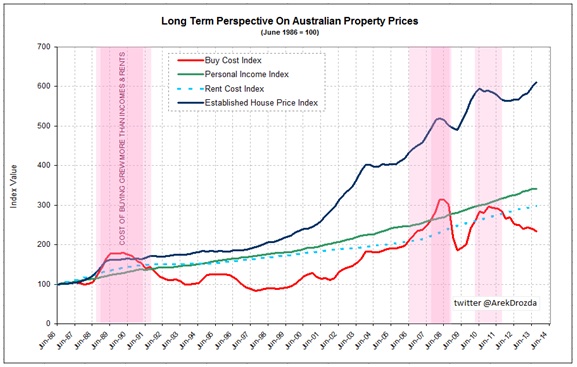

Testing the theory that all of these interconnected indicators provide a markedly different picture as to the state of housing affordability in Australia, Drozda published his findings in Property Observer at the beginning of 2014.

Source – Arek Drozda in Property Observer, based on ABS data

Drozda’s findings reveal that even though property prices have increased six-fold in Australia since the mid-eighties, the cost of purchasing a median priced house has risen less than two and a half times for the same period.

In fact, the increase in personal incomes has been substantially higher over the last three decades, than the corresponding rise in the cost of buying and renting. In other words, buying a house today is actually more affordable than it was almost 30 years ago.

So next time your adult son or daughter complain about the baby boomer generation exerting too much pressure on the housing markets and making their Great Australian dream of home ownership unattainable, maybe you should sit them down and show them a more balanced perspective.