Amid growing concerns that Australia’s housing markets are tipping toward a property ownership imbalance, regulators are getting serious about stepping in to slow down the property investment juggernaut.

Some suggest we are now witnessing the side effect of a surge in speculative activity on the part of future retirees, looking to cash in on “generous tax incentives” for Aussie landlords.

These so-called “speculative investors” have drawn the spotlight in today’s swelling wave of market activity. Interestingly, the Reserve Bank of Australia released an article in its September Financial Stability Review, citing the characteristics of Australian property investors and how they’ve changed over time.

Who are these investors?

Using data from the ATO and the Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey, the Central Bank tracked changes to the market and its composition.

The report determined that investors are more likely to take risks with their property acquisitions than owner-occupiers, because of our “favourable tax environment” – i.e. negative gearing policies.

For instance property investors, “have stronger incentives than owner-occupiers to take out interest-only loans”. Sixty four per cent of all IO loans were attributed to investors between 2008 and 2014, compared with just 31 per cent for owner-occupiers. (See below chart)

Some say the reason is obvious; interest expenses are a tax deduction for property investors, so an IO loan maximises that deduction. Conversely, owner-occupiers take up these loans to save on costs in those first few years of home ownership.

Really though, does this not amount to the same thing for both purchaser groups? Saving money? Saving costs on your loan? So why are investors copping such a hard time? Particularly when the government has incentivized property investment with various policy and regulatory reviews over the last few decades.

And while we’re discussing risk, what about the fact that property investors are more likely, according to the RBA report, to hold a lower loan-to-value-ratio than owner-occupier borrowers, thereby reducing their debt exposure?

Investors versus owner-occupiers versus tenants

Owner-occupiers, tenants (who apparently all want to own a home) and investors are being pitted against one another, in the battle for affordable accommodation on the one hand and a decent retirement fund on the other.

This is being fuelled by media commentaries that teeter on the precipice of scapegoating; with property investors targeted as the primary cause for the latest upward market swing and shift in traditional Australian property ownership ratios.

Analysts have cited the current low interest rate environment and hype around SMSFs, along with favourable tax treatment of income derived from real estate assets, as the reason for investors dominating major capital city markets across Australia for the last 24 months. Oh, and of course, housing affordability.

But really, Australia has long been an anomaly among the rest of the developed world when it comes to our traditional, 70 per cent home ownership statistic. So could it be that we are starting to catch up, with that figure now sitting at 67 per cent?

Or perhaps, how we live and the things we prioritise in our life are changing? People are starting families when they’re older, travelling more in an ever-accessible global world and focusing on climbing the corporate ladder.

For some, perhaps being a tenant does not represent an inescapable Hell you’re forever stuck in because you cannot buy a home. Instead, it might represent freedom from the constraints of home ownership.

Anecdotally, we’re seeing an increasing number of investors who choose to happily remain renters, whilst building their own property investment portfolio.

So is it really such a bad thing that property investment is increasing in popularity? Is the current investor juggernaut the harbinger of doom for our property markets? Or does it reflect a larger shift in how we think about managing our own future retirement funds?

Forced slow down imminent?

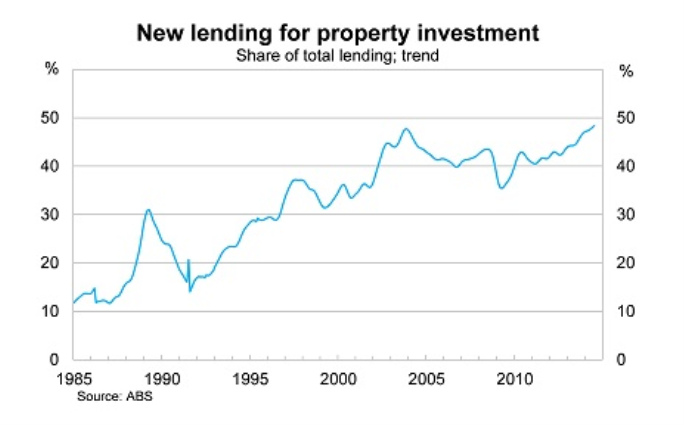

Irrespective of its root cause, the RBA is becoming increasingly concerned with the amount of new investor lending activity over the past few years. The below graph demonstrates a spike from around 2011, with similar peaks apparent around 1990, the end of the last decade and between 2002-2005.

The banking regulator is not entirely convinced that this lending represents a systemic risk, noting most of the “risks associated with lending behaviour are likely to be macroeconomic in nature”.

However, it says the broader risk remains due to the $5 trillion tied up in property assets, which accounts for the majority of household wealth and essentially the lifeline for banking sector profits in Australia.

Concerns over this increasingly “imbalanced lending activity” are now driving the RBA and the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA), to consider the introduction of macroprudential policies to take some of the steam off property investor activity.

Many experts suggest this couldn’t come soon enough, with prices continuing to rise sharply across Sydney in particular.

It’s anticipated that the two financial authorities may introduce alternative measures to slow lending in lieu of monetary policy, given their continuing quandary with interest rates and inflation.

With Australian banks among the most leveraged financial institutions in the word, you can understand the RBA and APRA feeling a little skittish about the potential for the wheels to fall off, should the property market swing too far in one direction.

For instance, what happens to all the investment properties those asset-rich, cash-poor baby boomers purchased early last decade (when they were 40-something)?

Those same baby boomers that are now edging closer to a time when they will perhaps need to liquefy a property or two in order to pay for their retirement? Given affordability is already an issue for young Australians, who will have the necessary buying power to purchase that housing stock?

These questions have obviously weighed on RBA Governor Glenn Stevens’ mind of late, with him recently suggesting that baby boomers would do well to diversify their asset holdings.

The RBA and APRA have the backing of the Australian government, with Treasurer Joe Hockey giving them the green light to pursue a broader set of policies.

The RBA would not be alone in pursuing this type of intervention, with other world banking regulators taking their own action to exert some force in order to shift the fortunes of local property markets.

In June this year, the Bank of England introduced new rules under which only 15 per cent of new home loans will be allowed to have loan to income ratios of 4.5. This occurred on the back of the Reserve Bank of New Zealand introducing temporary restrictions on lending with higher LVR’s.

What could it be?

These sorts of changes to macroprudential policies in Australia are unlikely. Instead, it’s anticipated that such measures would be in the guise of enhanced interest rate buffers during periods when interest rates drop low.

Much ado will be made if such macroprudential policies get the go ahead here in Australia. Certainly, it could serve to make the growing issue of home ownership for younger generations more problematic.

But experts say we must remember that this is not a move to address affordability, but to reduce the systemic risk within the financial sector.

Fixing the affordability barrier is a whole other ball game, requiring reform around supply and demand factors with all tiers of government addressing planning and zoning practices to create a more responsive housing supply chain. But that’s a debate for another day…